Topics in Applied Math: Methods

of Optimization

Math 5750-002/ 6880-002 , 3 credit hours. Fall 2011.

MWF 11:50-12:40, WEB 1450

Instructor :

Professor Andrej

Cherkaev,

Department of Mathematics

Office: JWB 225,

Email: cherk@math.utah.edu,

Tel : 801 - 581 6822

Text: Jorge Nocedal and

Stephen J. Wright. Numerical Optimization (2nd

ed.) Springer, 2006

Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12,13, 15, 16,

17.

Notes

Course is designed for

senior undergraduate and graduate students in Math, Science,

Engineering, and Mining

Prerequisite: Calculus, Linear

Algebra, Familiarity with elementary programming.

Grade will be based on weekly

homework, exams, and class presentations. M 6880 students will

be assigned an additional project.

Notes and Homework

Text for Introduction topic: SINGLE VARIABLE SEARCH TECHNIQUES

http://www.mpri.lsu.edu/textbook/Chapter5-b.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_section_search

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fibonacci_search_technique

Homework 1

Homework 2

Additional reading for Trust region method:

Notes 1 ,

Notes 2 ,

See also Matlab Optimization Toolbox and Mathematika tools ,

Homework 3

Homework 4

Two revevant research papers

J. E. Dennis, Jr. and Jorge J. Morέe. Quasi-Newton Methods, Motivation and Theory.

R. Chartrand, and V. Staneva. A quasi-Newton method for total variation

regularization of images corrupted by non-Gaussian noise.

Homework 5

Final exam FINAL

Good luck, everyone!

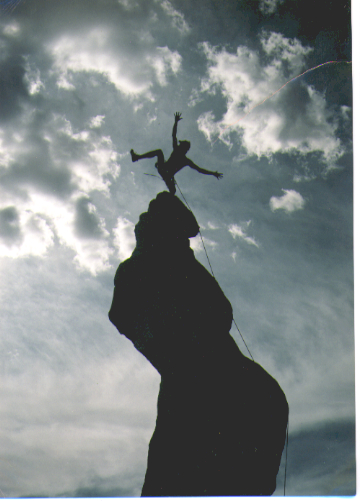

Optimization

The desire for optimality (perfection) is inherent for

humans.

The search for extremes inspires mountaineers, scientists,

mathematicians,

and the rest of the human race.

Search for Perfection:

An image from

Bridgeman Art

Library

A beautiful and practical optimization

theory was developed from the sixties when computers become

available. Every new generation

of computers allowed for attacking new types of problems and called for

new

optimization methods. The aims are reliable methods to fast approach

the extremum of a function of several variables by an intelligent

arrangement of its evaluations

(measurements). This theory is vitally important for modern engineering

and planning that incorporate optimization at every step of the

complicated

decision making process.

This course discusses various direct methods,

such as Gradient Method, Conjugate Gradients, Modified Newton

Method, methods

for constrained optimization, including Linear and Quadratic

Programming,

and others. We will also briefly review

genetic algorithms that

mimic evolution and stochastic algorithms that account for

uncertainties

of mathematical models. The course work includes several homework

assignments

that ask to implement the studied methods and a final project, that

will be orally presented in the class.

Contents

Plan

Remarks, Introduction: About

the algorithms, Optimization and modeling, Basic

rules, Classification

Links

Go to the top

Introduction. Ch 1, 2

Line search methods Ch.3

Trust region methods Ch. 4

Conjugate gradient method Ch. 5

Quasi-Newton methods. Ch. 6

Large-scale problems and calculation of derivatives. Ch. 7, 8

Derivative-free optimization. Noise. Ch 9

Least-square problems. Ch 10

Constrained Optimization. Ch 12

Linear Programming. Ch. 13

Nonlinear Constrained Optinization. Ch 15

Quadratic programming. Ch 16

Penalty and Augmented Lagrangina Method. Ch 17

Projects presentation

Review of various methods (2 week)

Stochastic search. Genetic algorithms. Discrete methods. Minimax and

games.

Reserve (1 week).

Go to the top

Remarks on Optimization

The desire for optimality (perfection) is inherent for humans. The

search for extremes inspires mountaineers, scientists, mathematicians,

and the rest of the human race. A beautiful and practical mathematical

theory of optimization (i.e. search-for-optimum strategies) is developed

since the sixties when computers become available. Every new generation

of computers allows for attacking new types of problems and calls for new

methods. The goal of the theory is the creation of reliable methods to

catch the extremum of a function by an intelligent arrangement of its evaluations

(measurements). This theory is vitally important for modern engineering

and planning that incorporate optimization at every step of the complicated

decision making process.

|

Optimization and aestetics

The inherent human desire to optimize is cerebrated in the famous Dante

quotation:

All that is superfluous displeases God and

Nature

All that displeases God and Nature is evil.

In engineering, optimal projects are considered beautiful and rational,

and the far-from-optimal ones are called ugly and meaningless. Obviously,

every engineer tries to create the best project and he/she relies on optimization

methods to achieve the goal. |

|

Optimization and Nature

The general principle by Maupertuis

proclaims:

If there occur some changes in nature, the

amount of action necessary for this change must be as small as possible.

This principle proclaims that the nature always finds the

"best" way to reach a goal. It leads to an interesting inverse optimization

problem: Find the essence of optimality of a natural "project." |

The essence of an optimization problem is: Catching

a black cat in a dark room in minimal time.

(A constrained optimization

problem corresponds to a room full of furniture.)

A light, even dim, is needed: Hence optimization methods explore assumptions

about the character of response of the goal function to varying parameters

and suggest the best way to change them. The variety of a priori assumptions

corresponds

to the variety of optimization methods. This variety explains why there

is no silver bullet in optimization theory. |

|

Semantics

Optimization theory is developed by ingenious and creative people,

who regularly appeal to vivid common sense associations, formulating them

in a general mathematical form. For instance, the theory steers numerical

searches through

canyons

and passes (saddles), towards the

peaks;

it fights the curse of dimensionality,

models

evolution,

gambling,

and other human passions. The optimizing algorithms themselves are mathematical

models of intellectual and intuitive decision making.

Go to the top

Introduction to Optimization

Everyone who studied calculus knows that an extremum of a smooth function

is reached at a stationary point where its gradient vanishes. Some may

also remember the Weierstrass theorem which proclaims that the minimum

and the maximum of a function in a closed finite domain do exist. Does

this mean that the problem is solved?

A small thing remains: To actually find that maximum. This problem is

the subject of the optimization theory that deals with algorithms

for search of the extremum. More precisely, we are looking for an algorithm

to approach a proximity of this maximum and we are allowed to evaluate

the function (to measure it) in a finite number of points. Below, some

links to mathematical societies and group in optimization are placed that

testify how popular the optimization theory is today: Many hundreds of

groups are intensively working on it.

Go to the top

Optimization and Modeling

The modeling of the optimizing process is

conducted along with the optimization. Inaccuracy of the model is emphasized

in optimization problem, since optimization usually brings the control

parameters to the edge, where a model may fail to accurately describe the

prototype. For example, when a linearized model is optimized, the optimum

often corresponds to infinite value of the linearized control. (Click

here to see an example) On the other hand, the roughness of the model

should not be viewed as a negative factor, since the simplicity of a model

is as important as the accuracy. Recall the joke about the most accurate

geographical map: It is done in the 1:1 scale.

Unlike the models of a physical phenomena, an optimization models critically

depend on designer's will. Firstly, different aspects of the process

are emphasized or neglected depending on the optimization goal. Secondly,

it is not easy to set the goal and the specific constrains for optimization.

Naturally, one wants to produce more goods, with lowest cost

and highest quality. To optimize the production, one either may constrain

by some level the cost and the quality and maximize the quantity, or constrain

the quantity and quality and minimize the cost, or constrain the quantity

and the cost and maximize the quality. There is no way to avoid the difficult

choice of the values of constraints. The mathematical tricks go not

farther than: "Better be healthy and wealthy than poor and ill". True,

still not too exciting.

The maximization of the monetary profit solves the problem to some extent

by applying an universal criterion. Still, the short-term and long-term

profits require very different strategies; and it is necessary to assign

the level of insurance, to account for possible market variations, etc.

These variables must be a priori assigned by the researcher.

Sometimes, a solution of an optimization problem shows unexpected features:

for example, an optimal trajectory zigzags infinitely often. Such behavior

points to an unexpected, but optimal behavior of the solution. It should

not be rejected as a mathematical extravaganza, but thought through! (Click

here for some discussion.)

Go to the top

Basic rules for optimization algorithms

There is no smart algorithm for choosing the oldest

person from an alphabetical telephone directory.

This says that some properties of the maximized function be a priori assumed.

Without assumptions, no rational algorithms can be suggested. The search

methods approximate -- directly or indirectly -- the behavior of the function

in the neighborhood of measurements. The approximation is based on the

assumed smoothness or sometimes the

convexity

Various methods assume different types of the approximation.

My maximum is higher than your maximum!

Generally, there are no ways to predict the behavior of the function everywhere

in the permitted domain. An optimized function may have more than one local

maximum. Most of the methods pilot the search to a local maximum without

a guarantee that this maximum is also a global one. Those methods that

guarantee the global character of the maximum, require additional assumptions

as the convexity.

Several classical optimization problems serve as testing grounds for optimization

algorithms. Those are: maximum of an one-dimensional

unimodal function, the mean square approximation, linear

and

quadratic

programming.

Go to the top

Classification

To explain how knotty the optimization problems are, one may try to classify

them. I recommend to look at the optimization

tree by NEOS.

Below, there are some comments and examples

of optimization problems.

-

Numerous optimization methods are designed for various number

of independent controls (dimensionality). These ranges corresponds

to one variable, several (two to ten), dozens, hundreds, or tens of thousands.

-

An important special class -- discrete optimization

-- corresponds to a large number of controls that take only integer or

Boolean values. It requires combinatorial methods.

-

Another special case --

calculus

of variations -- corresponds to infinitely many controls.

-

A significant parameter is the cost of evaluation

of the function: It ranges from milliseconds of the computer time to lengthy

and costly measurements in natural experiments. Accordingly, the realistic

goals and the methods are different.

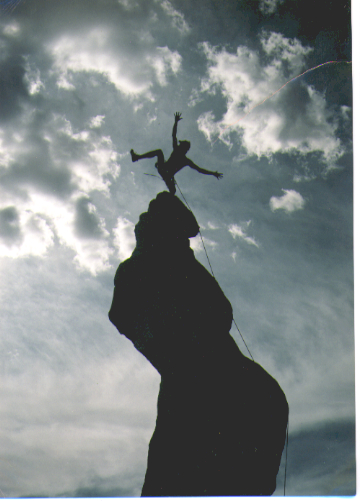

Sharp Maximum is achieved!

The photo by and courtesy of

Dr. Robert (Bob) Palais |

The sharpness of the maximum is

of a special interest. It is very difficult to find a maximum of a flat

function especially in the presence of numerical errors. For instance,

a point of the maximum elevation in a flat region is much harder

to determine than to locate a peak in the mountains. A sharp maximum

(left figure) also requires some special methods since the gradient

is discontinuous; it does not exist in the optimal point. |

-

The presence of constraints and their character is very important for the

choice of the strategy. The constrained problem

typically possess the sharp maximum in a corner of the permitted domain

while the smooth unconstrained function reaches its maximum in a stationary

point.

-

Stochastic optimization deals

with noise in measurements or uncertainty of some factors in the model.

The optimization process should account for possibly non accurate data

(click

here to see an example). Here, the goal may be to maximize the expected

gain or to maximize the probability of the high profit.

-

Another approach asks to play the game: Design versus Uncertainty, considering

for the worst possible scenario. Find here an

example of such game.

Structural

Optimization is an interesting and tricky class of optimization problem.

It is characterized by a large number of variables that represent the shape

of the design and and stiffness of the available materials.

The control is the layout of the materials in the volume of the structure. |

|

In any practical problem, the researcher meets a unique combination of

mentioned factors and has to decide what numerical tools to use or modify

to reach the goal. Therefore, the optimization always includes creativity

and intuition. It is said that optimization belongs to both science and

art.

Go to the top

Go to Contents

Go to the top

Go to

Teaching Page

Go to my Homepage

NSF support is acknowledged.